"All things in life are sweetened by risk"

Alexander Smith 1830-1867

To Canada and back (well.....almost!) on a wing and a prayer 10th - 17th July 2009 |

|

Prologue Like many hare-brained ideas, this one was formulated in the pub, having had one too many beers after a day’s flying. My friend and fellow pilot, Paul Yates had wanted to fly the North Atlantic in a single-engined light aircraft for some considerable time. Why??..... ”Because it’s there!” Paul taught me to fly in 2004; we’ve had many escapades and have become firm friends in the time since then. Paul’s a real adventurer and I’ve spent the last few years trying to match all of his derring-do so I hijacked the idea and, as I had recently acquired a perfectly serviceable aeroplane, we had the means to stop talking about it and actually do it. The conversation in the pub took place a couple of years ago and we were initially going to try to undertake the trip in an Antonov AN2 which we’d (unwisely) bought together and which nearly bankrupted us. (See www.paulsquires.co.uk/Antonovslideshow.html ) The AN2 is a fantastic aircraft and draws a crowd wherever it goes but its fuel burn made it a rather uneconomical proposition for two ordinary working guys. Having an aeroplane and not being able to afford to fly it is very frustrating and we eventually sold the Ant. It’s now doing pleasure flights in the Swiss Alps but that’s another story…..

Our Antonov AN-2. Now sold to Switzerland We bought the Lithuanian registered Antonov AN2 in 2006 (my ‘in-at-the-deep-end’ introduction to tailwheel aircraft) and went to Lithuania to undergo vodka-fuelled, type rating training at the hands of eccentric but highly skilled Eastern European pilots (but that too is another story!) During our time in Lithuania, we became fascinated by the story of Pilots Steponas Darius and Stasys Girenas – Lithuanian emigrants to America who, in 1933, attempted a non-stop flight from New York to Kaunas, Lithuania, in a modified single-engined Bellanca. Unfortunately, their attempt ended in tragedy when both pilots were killed as their aircraft crashed in Germany - the cause of the crash is still a mystery. Although the attempt didn’t fully succeed, Darius and Girenas became National heroes: they have museums and stadia named after them and their faces adorn the back of Lithuanian coins and banknotes even today.

Banknotes, coins and stamps commemerate the 1933 Trans-Atlantic flight of Darius and Girenas The combination of a trans-Atlantic flight and possibly trying to re-enact the flight of Darius and Girenas (hopefully without the tragic ending!) held tremendous appeal for us but regrettably we had to sell the Ant before we could undertake the trip so our 2008 attempt was scrubbed before we even started detailed planning.

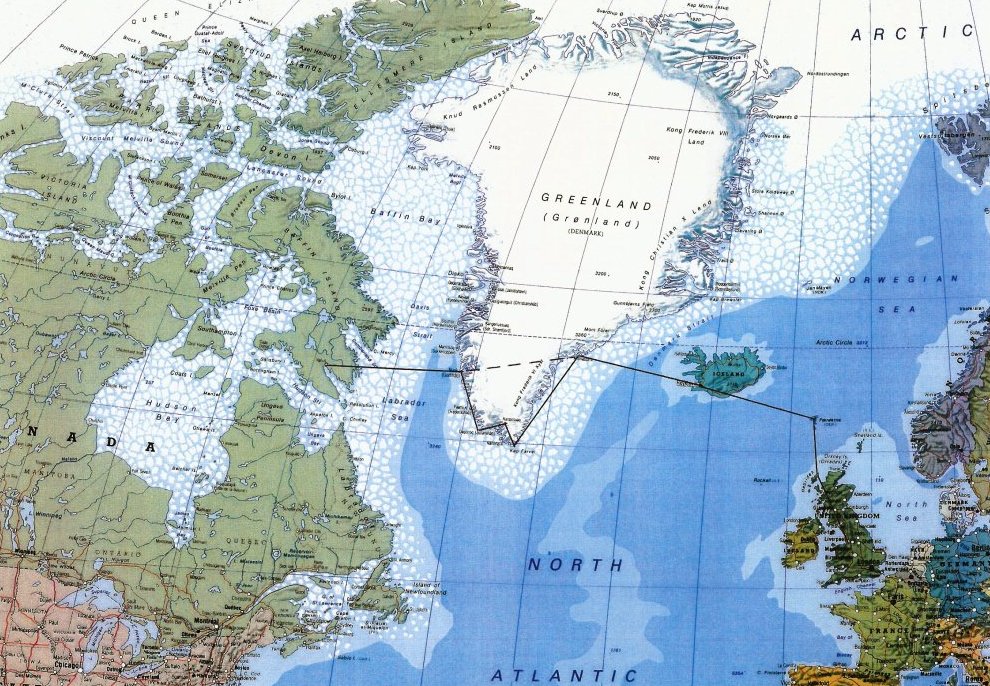

My new aircraft - a six seat Piper Saratoga Track forward to 2009 and I am now the proud owner of a 1981 Piper Saratoga which we think is the perfect aircraft to undertake the trip. However, try as we might, it proves all but impossible to get a ferry tank fitted to the aircraft in an ‘approved’ way. This seems madness to me as, having removed the rear four seats and lifted the flooring, the fuel pipes and fuel pump are clearly visible, as is the joint which is tailor-made for a ferry tank to be plumbed in (how do you think these American manufactured aircraft get to Europe in the first place?) It would be a temporary modification, not a permanent one but bureaucracy and paperwork thwart us (why do the FAA seem to be so much more pragmatic than our CAA?) and we are left with the dilemma of making an unauthorised mod by fitting a tank ourselves (which I know a lot of people do) or radically altering our routing by ‘land-hopping’ rather than going straight across the water. Given that an unauthorised modification will likely invalidate any insurance and could cause problems if we are ramp-checked at our destination, we elect to land-hop. The more we think about it, the more the new routing appeals as we’ll get to land at airfields we’d never normally visit, drink foreign beer, meet interesting people and generally be better entertained than we would be looking at nothing but water for 30 plus hours (there and back). However, if we’re not going straight across the water, the re-enactment of the Darius and Girenas trip will have to wait for another time (when we’ve a little more money or if we find a wealthy sponsor! ) and we’ll set our sights a little lower by just aiming to get across the North Atlantic and back in one piece. We agree that one of us will fly the outward trip and the other will fly back so that we can each lay claim to having flown the North Atlantic single-handed if not solo. The revised routing is Liverpool (EGGP) – Stornoway (EGPO)– Vagar (Faroe Islands) (EKVG) – Reykjavik (BIRK) – Kulusuk (Eastern Greenland) (BGKK) – Narsarsuaq (Southern Greenland) (BGBW)– Nuuk (Western Greenland) (BGGH)– Iqaluit (CYFB) (Northern Canada). Some 5000 nautical miles over terrain which our VFR flying in the UK has certainly not prepared us for but it doesn’t look that far on the map and how hard can it be??.....

Our intended routing Even though we’re now land-hopping, there’s a lot of water to cross on our intended route so we attend a safety course at Fleetwood Nautical College and enjoy a day of ‘dunking’ or HUET training (Helicopter Underwater Evacuation Training) involving getting dunked – upright and inverted – in a mock aircraft fuselage and deploying and climbing into a life raft. The course we attend is really aimed at those employees going onto the North Sea oil and gas platforms but it gives us a taste of what we might expect if we were to have to ditch. It’s a lot harder than it looks (even in the tepid, Health and Safety, temperature-controlled water) and I begin to wonder how I would cope if there were a real emergency and we were down and hyperventilating in the freezing cold, hostile waters of the North Atlantic.

The 'Dunker' on its side in the pool at Fleetwood Nautical College / The 3 Stooges. What do these guys look like!? Paul S, our friend Moore and Paul Y - HUET training complete Although we’re not carrying a ferry tank, we’ve elected to take out the rear 4 seats as we’ll be carrying quite a bit of kit. We have not one, but two, liferafts (one for personal use and one to inflate inside the airframe to keep it afloat if we ditch) and LOTS of provisions. We’ve got one-man self-erecting tents, gallons of water, spare tyres for the nosewheel and the mainwheels, a jack, a comprehensive tool set, sleeping bags, food and every conceivable chart for the airspace we’ll be overflying. We’ve also got EPIRBs and a rented satellite phone which has an aerial which we can dangle out of the DV window to get a signal (wouldn’t work in a high wing Cessna). We’ve got the Satphone instead of HF radio which we’ve been told is of limited use for our intended route and altitude. We’ve tested out the Satphone before departure and it works well. Provided we survive the impact, it will almost certainly give us comms whether we find ourselves in a raft or on a mountainside. We think we’re prepared for anything but we are soon to discover otherwise. In addition to getting together a comprehensive kit inventory, there’s an awful lot of other planning to do. We’ve confirmed that we don’t need overflight permissions but it’s not a bad idea to get in touch with each airfield and try to determine if there are any local issues to contend with. The internet and e-mail are invaluable tools and I fire off e-mails to all of the airfields which we are intending to land at to try to determine landing fees, cost of fuel etc. Some of the responses are very warm and friendly, particularly from Vagar and Reykjavik and I build a portfolio of charts and airfield details. Some of the airfields have their own website which is quite useful and I download PDFs of NavCanada’s Airport Charts and the Danish and Icelandic AIP. I also order a Jeppesen Trip Kit covering the intended route. Insurance is an issue too. A typical travel insurance policy won’t give us the cover we require but, after much trawling of the internet and many telephone calls, I find an insurance broker who can arrange personal accident and life assurance cover for the trip. The problem is that no-one seems to want to insure pilots doing this sort of thing unless they are experienced ferry pilots but how do you get the experience if you can’t get the insurance to fly? We could fly uninsured but our Families are not best pleased about us undertaking this little jaunt and leaving them without financial support in the event of a mishap would be even more selfish of us. A similar problem arises with the aircraft insurance. Most UK aviation insurance policies for GA aircraft have geographical limits which extend as far as Iceland but not beyond. This is something which we absolutely must have – I don’t fancy bumping into a 737 at Nuuk and having no 3rd party insurance. I also don’t like the idea of being ramp-checked somewhere and having my aircraft impounded as we are flying illegally without insurance! Happily, after some initial resistance, I manage to convince the insurance underwriter that there is a better than 50/50 chance we will be coming back and he grudgingly adds an endorsement to the policy to extend the geographical limits for 2 weeks. Neither the personal insurance nor the aircraft insurance extension are inexpensive but they’re essential. We’re over our budget already and we haven’t bought a drop of fuel! We decide that we should try to raise some funds for charity rather than doing the trip purely for self-indulgent reasons and so we circulate sponsorship forms detailing the intended route and asking for donations which will allow the donors to enter a competition to guess the nautical miles flown and the time taken for our intended routing. The prize is an hour’s flight for two in the Piper Saratoga around the Lake District. We hope it will generate some interest for our chosen charity - Rosemere Cancer Foundation (see www.rosemere.org.uk ) - who offer care to cancer sufferers at Preston Royal Hospital. Day 1 – 10th July 2009. Total flying time 7 hours 13 minutes – total distance 981.4 NM Liverpool to Stornoway – 2 hours 31 minutes – 324.7 NM

Suited up and ready to depart from Liverpool - Paul Yates (L) & Paul Squires (R) Our trip begins without much fanfare, but with some trepidation on the part of our Families (and with only slightly less trepidation on the part of the pilots!) on a nondescript Friday morning from Liverpool John Lennon Airport. We depart at 10.00 local time (09.00 UTC) after a few photos in our immersion suits. The intention is to try to get to Iceland on the first day so we feel like we’re making progress and by then, we’ll have done enough flying to wipe away any initial nervousness about the magnitude of the journey we’re undertaking. The first leg to Stornoway is relatively uneventful and is almost a straight line North. We talk to Warton Radar and then to Scottish Information as we near the FIR boundary. I fly this leg and approach Stornoway for a straight in landing on runway 36. The autopilot is working well and I let the aircraft do the work by flying a coupled approach to 500 feet on the localiser. The landing is OK and we taxi in for fuel.

Coupled approach to Stornoway Runway 36 / Stornoway tower and refueller The guys in the tower are very helpful and seem genuinely interested and a little bemused by what we’re planning to do. They get some ferry pilots through here but they rarely get two idiots who are planning to fly to Canada VFR and back just for kicks. I ask how long we need to delay before filing our VFR flightplan and setting off and I’m told (as eventually, I will be at every stop) that we can go immediately - the implication being that filing a VFR flightplan is a fairly futile exercise anyway and nobody seems to care very much about what you’re doing so long as you don’t mix it with the big boys flying airways. We agree that, having left the UK, Paul Y will fly the outward leg from Stornoway to Iqaluit and I will fly back West to East. However, I’m flying left seat there and back as I feel more comfortable there. Paul is unruffled by this – he’s an instructor/examiner and so he’s used to flying from the right seat. Unfortunately, with thoughts of ditching ever present, I’m extremely conscious of the fact that there’s only one door at the front of the Saratoga and it’s on his side. Eventually, I convince myself that, even in my bulky immersion suit, I’d be over the front seats, into the rear of the aircraft and out of the rear door in the case of a ditching. It’s amazing what a bit of training combined with a rush of adrenaline makes one capable of – let’s just hope I don’t have to test the theory! We launch off on runway 36 and head North West for our first long leg over water to Vagar in the Faeroe Islands. Stornoway to Vagar – I hour 50 minutes – 236.1 NM We approach Vagar VFR ‘on top’ at 4000 feet and descend to 2000 feet through a hole in the clouds. As we approach Vagar, we have a minor disagreement about the location of the airfield. We’ve got more than enough GPS equipment on board to hopefully avoid any confusion (a panel-mounted Garmin 430, and a yolk mounted 496 on the left column with the older 296 on the right side). Prior to departure and at considerable cost, all the GPS databases have been updated to the current cycle. Notwithstanding the presence of all this kit, Paul never puts complete trust in technology so we’re doing it the old fashioned way and trying to match the land features which we can now see out of the cockpit with the visual approach chart for Vagar which I’ve downloaded from the Danish AIP. There are so many small islands and inlets, it’s very easy to get confused even in good visibility. Given that we are on a VFR approach to Vagar, it makes you wonder what would happen if the weather closed in; flying around trying to get your bearings in poor viz with all those cliff faces and steep hills is not recommended. We’d struggle to get to Reykjavik as an alternate and we’d be on minimum reserves if we were to try to get back to Stornoway. Anything like a decent headwind if we had to do a 180 would be likely to put us in the drink. Thanks once again to the CAA for making it so difficult to fit an approved additional fuel tank! If we ditch and drown, I swear I’m coming back to haunt the CAA HQ building at Gatwick!!

Faroes map / approach to Runway 31 at Vagar We finally agree which hole in the hills to fly through and happily, we are both right (and the GPS concurs) and we are rewarded with a view of Vagar airfield which shows us set up for a straight in approach to the 1250m Rwy 31. We’ve no intention of staying as we think we may stay overnight on the return leg; right now, we just want to get some distance behind us so we want to get a quick turnaround. Paul arranges for fuel whilst I go up to the tower to get the weather for Reykjavik, a stamp in our logbooks, sort out the landing fees and file another pointless VFR flightplan. The landing fee is payable in Danish Kroner but we don’t have any and their credit card machine isn’t working so, instead of us going to the main terminal building to the Bureau de Change, the chap in the tower takes some Sterling from us, does a rough currency conversion and gives us change in Danish Kroner (which he then, helpfully explains we will be unable to use at our next stop in Iceland but will be able to use in Greenland).

Vagar Airport

Mike Tango refuelled and waiting to go in front of the Control Tower Once we’ve dealt with formalities in the tower, we waste about 30 minutes going backwards and forwards through the revolving door in the ‘Arrivals’ hall to see a chap in a uniform who Paul has been told by the refueller will need to see our passports. When we go to the arrivals hall initially, he’s not there. We don’t want to become international fugitives so we don’t want to launch off before we’ve handed in our passports for inspection. On the other hand, we want to get going and having rushed to refuel and deal with the Tower, this bureaucracy is a little irritating. Yes, we’ve landed, but we’re not even staying or going anywhere other than the airfield. The ‘Uniform’ eventually turns up (he’s probably been on his tea break) and after scrutinising our passport photos and the two harassed, immersion-suited individuals before him, he graciously concedes that there might be sufficient passing resemblance between the two to allow us to continue with our journey. Within an hour (which could easily have been 20 minutes without all the messing about) we’re airborne again and heading West to Iceland.

A Vagar fire engine. We may well need one of these later in the trip! Vagar to Reykjavik – 2 hours 52 minutes – 420.6 NM As we depart Vagar, we get an idea of how small a community it is. The town is very small indeed and there don’t seem to be many buildings outside the main town which is built just around the edge of the airfield. We also get a very close look at some extremely jagged peaks which seem a little too close to our departure path for comfort. This is not like flying in the Home Counties!

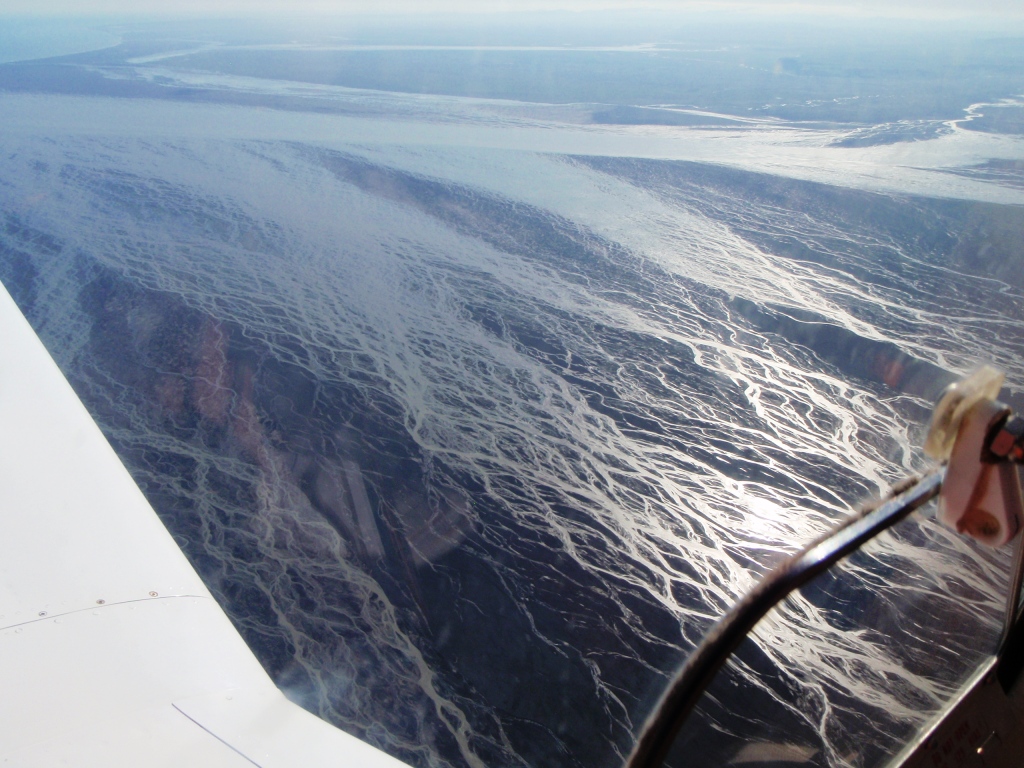

Vagar Town / On the climbout from Vagar We want to get a little height and climb to 6000 feet but at this level we are flying VMC on top of nearly 8/8 cloud cover. The unbroken cloud cover is rather reassuring as we can’t see the sea! It continues for almost all the way to Iceland and then begins to break up so we get a good view of the approaching Icelandic coastline. The last time Paul Y saw Iceland, it was from the bridge of a Grimsby deep-sea trawler during the last Cod War! We’re trying to raise Reykjavik and aren’t having much luck but manage to get a message relayed to them. As we coast in we begin to see how spectacular the Icelandic scenery is – glaciers, silt-laden, turquoise lakes, black and purple mountain peaks and not a sign of civilisation for miles. The other thing we begin to realise is how large Iceland actually is. We seem to have been flying for ages since reaching land but we hardly seem to have moved on the GPS against the Iceland background map. Initially, we were relieved to have the sea behind us but looking at the terrain around us, it would seem that there would be very few places we could carry out a landing if the engine packed in. On reflection, we’d probably have a better chance of surviving a ditching than if we went down here and Reykjavik’s still some way off. These sorts of thoughts were to become quite wearing over the next few days as we encountered more and more hostile terrain. The only thing to do is switch off and keep taking photos!

8/8ths cloud cover. VFR 'on top'

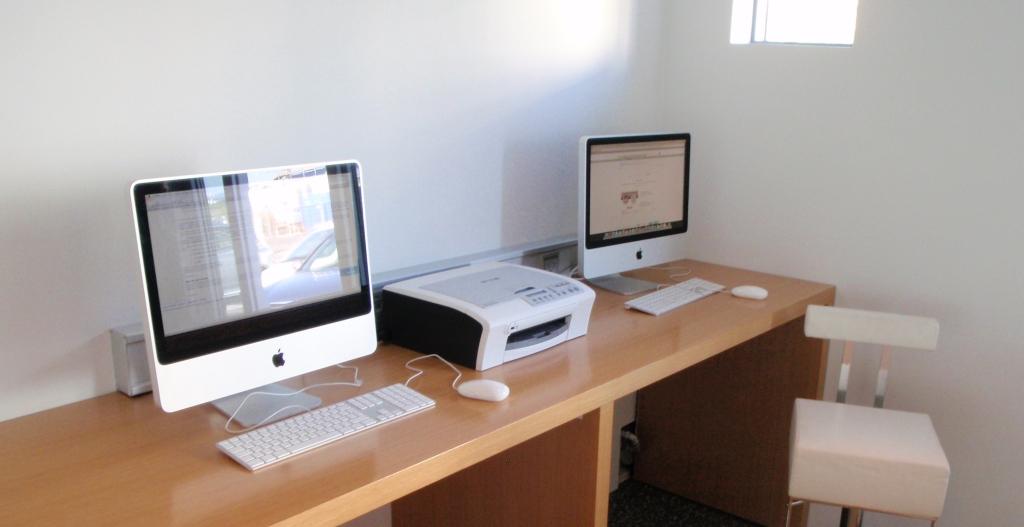

3 examples of Icelandic terrain / Reykjavik We are talking to Reykjavik approach and are asked to report the field in sight. We get to within 3 miles and still can’t see it. It’s almost as though, having stared at the wild scenery of the Icelandic countryside for over an hour, our brains just can’t make sense of an urban landscape. The controller sounds rather exasperated when we admit we’re still not visual and confirms that we’re cleared to land on runway 27 which should be right on our nose. We continue, knowing that we can see the sea on the other side of the town and the worst that can happen is that we overfly the airfield and have to fly a circuit. We become visual at about 1.5 miles and approach rather more steeply than would be usual but Paul puts us down without any fuss and we taxi to Birk Flight Services who handle all incoming GA flights. We land at 18.09 local time (which, as Iceland is 1 hour behind UK BST, is the same as UTC). I have to say that the service at Birk Flight Services when we arrive is excellent. They sort out all the formalities, arrange for a customs officer to come to us, record details of our ongoing flight and undertake to get the weather for us, sort out a refuel, book us into a hotel and would even sort out taxis etc should we require them to get into town - all charged to our account and dealt with as one payment when we depart. They’ve got first class facilities – drinks are free and even the preflight planning can be done from leather chairs on a couple of top-end, superfast, wide screen Apple Macs. The hotel is a 4 star one, belongs to the airport authority and is 50 yards from the apron so we can get an early start tomorrow. I have to say that when compared to the facilities for GA pilots at most airfields in the UK, this feels more like a different planet rather than just a different country. The fuel is the cheapest we will uplift for the whole journey but the 180 Euro customs fee is a bit of a shock and seems quite excessive just to have someone look at our passports.

BIRK Flight Services reception with ATC tower and the airport hotel at the rear

Apple Macs for flight planning at BIRK Flight Services We gratefully get out of our (now smelly after 9 hours) immersion suits, check into the hotel to get cleaned up and, as will become our norm everywhere we visit, go out on the town. Day 2 – Saturday 11th July - Reykjavik The weather in Greenland is not favourable as there’s fog at Kulusuk which isn’t forecast to clear. We have insufficient fuel to go, make an approach and return so we can’t go. The only alternative is to try for Narsarsuaq but this requires 103 US gallons of fuel with no reserve and we carry 102 gallons! (wouldn’t a ferry tank be ever so useful?!?) So, we’re stuck on the ground in Reykjavik. However, based on what we found the previous evening, it’s not a bad place to stay. We’d been out to see some of the city and had only got back to the hotel at about 04.00. Icelandic people seem to know how to have a good time. There’s a vibrant atmosphere about Reykjavik and it never goes completely dark here at this time of year so places seem to stay open longer. The way some people are partying and spending money you’d never know that the country is nearly bankrupt and the banking system is in meltdown. Maybe they’re just having one last big party before the country disappears around the u-bend but it’s a good atmosphere which we get caught up in. We drink a little too much and get far too little sleep so it’s perhaps fortuitous that the weather prevents us from flying on Saturday. We’ve only been out for one day and we’re misbehaving already! We should get some sleep during the day but we go souvenir shopping instead and go around the town and down to the harbour to do the usual tourist walkabout. There’s a rusting fleet of whalers there and we climb aboard one for some pictures. There are also a couple of Icelandic gunboats moored there and Paul remarks that it’s the first time he’s seen one which didn’t have its guns pointed in his direction. More Cod War stories ensue over a couple of beers.

Icelandic Coastguard gunboats / 2 old examples of the Icelandic whaling fleet / On the deck of the whaler Day 3 – Sunday 12th July – STILL Reykjavik The aircraft is fuelled up (thanks to BIRK Flight Services), oiled up and ready to go. The fog in Kulusuk has lifted and the weather is good but we still can’t get in the air as it would appear that Greenland is closed!! They don’t allow flights into Greenland on Sundays. How did we miss something as fundamental as that in our planning and how come, of all the people we spoke to who had been there, no-one mentioned this important little piece of information? Kulusuk Airfield would be prepared to open up especially for us but would require an ‘out-of-hours’ fee of 900 US$. Needless to say, we are not impressed so we plan to stay for another day and depart at first light (whenever that is as it doesn’t go dark) tomorrow.

The only polar bears in Iceland are toy ones! / Norseman Another night of debauchery in downtown Reykjavik with live bands, Polar Beer and gorgeous women! We did learn one valuable lesson – do NOT order the Reindeer burger with Icelandic blue cheese. It seemed to disagree with Paul Y’s internal workings and he can now write a tour guide on Reykjavik public conveniences! Day 4 – Monday 13th July. Total flying time 5 hours 53 minutes – total distance 834 NM Reykjavik to Kulusuk – 2 hours 41 minutes – 398.8 NM The weather is flyable and Greenland has apparently re-opened. We taxi out at 09.30UTC. We have a birdstrike on takeoff just as the wheels are coming up. What looks like a seagull hits the leading edge of the port wing near the root but we elect to keep going rather than make a precautionary landing back at Reykjavik. There’s no evidence of any damage other than a bloodstain and a bit of seagull innards sticking to the wing and Paul confirms that the aircraft is handling normally. If the carcass has disappeared into the retracting gear, we’d have the same problem landing back at Reykjavik as we would at Kulusuk so there’s no point in not pressing on (but of course, at this stage, we have no idea of how rudimentary the facilities in Greenland are).

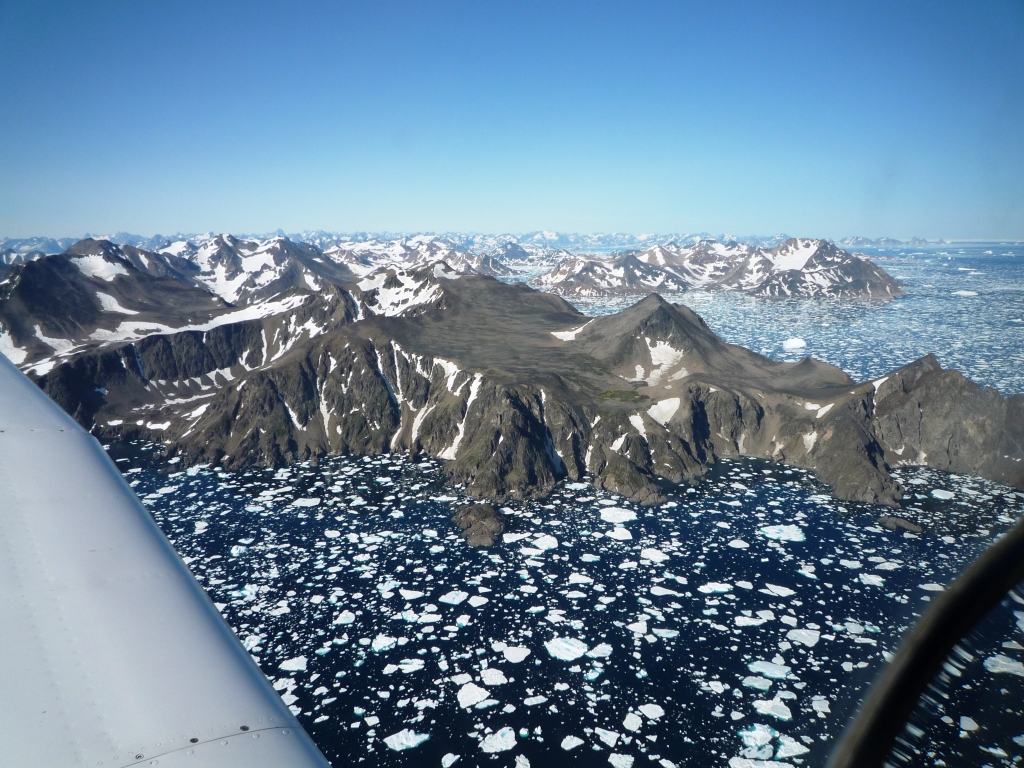

Satellite image of Greenland / Our first view of Greenland The visibility is crystal clear and after about 20 minutes flying we get our first views of the Greenland icepack and icebergs (although we initially thought some of the icebergs were cruise liners). As we draw closer, the views of the coastal mountains and the snow against the backdrop of the clear azure sky become more and more spectacular. The scenery in Iceland was very impressive but the terrain here is absolutely awesome.

Approaching Greenland - views from port and starboard With the benefit of almost perfect visibility, finding Kulusuk is not difficult but trying to pick out the brown gravel strip against the background is a little more tricky. We make a straight in approach to the gravel runway 29. The runway is undulating and the ‘gravel’ is really quite large stones which, worryingly, we hear bashing against the undercarriage and the underside of the airframe as we land. Clearly, this runway was not constructed with general aviation in mind. Air Greenland operate domestic flights through Kulusuk and Air Iceland route from Reykjavik to here. There’s one of their Fokker F50s unloading on the gravel apron as we taxi in.

The approach to runway 29 at Kulusuk - Can you see the runway yet? / There it is! As we taxi in, we both remark upon how desolate Kulusuk is. There appears to be only one hotel which is a wooden building a mile or so from the airfield. Kulusuk is not what you’d think of as a town – it’s more a settlement with wooden houses scattered around seemingly with very little planning or structure. There’s a population of only about 350 made up of Inuit Indians and Danish (as Greenland is Danish territory). We’re told that the population here wouldn’t be anywhere near as high if not for the airport which provides jobs for a number of the locals. We haven’t booked into the hotel (and, looking at the size of it, we’re not even sure we’d be able to get a room if even half the people who alighted from the Fokker are staying here) so we decide to press on to Narsarsuaq and take advantage of the weather.

Kulusuk terminal & tower / On the gravel apron at Kulusuk

Although the Human population is only 350,the mosquito population which descends on us is probably 350,000 and I’m pleased to be wearing my immersion suit which at least keeps most of me protected. For my head and hands, I’ve got insect repellent wipes and an Avon moisturising product called (would you believe?) “Skin so Soft” which allegedly acts as a more effective mosquito repellent than some of the tailor-made insect repellents. I’m not so much worried about my skin being soft as it not being new blood for the local insect population. Surprisingly, the Avon moisturiser seems to work for me but Paul refuses to rub any in and pays the price with several huge red lumps appearing on his neck in no time. He swears they even got him through his suit! We’d been warned about Greenlandic mozzies as they’re apparently a huge problem all over Greenland in the Summer months. We arrange a refuel and quickly seek refuge from the mosquitoes in the control tower. As was the case in both Vagar and Reykjavik, everyone here seems to speak good English. The two guys we meet in the tower are again extremely helpful regarding filing flight plans and getting all the relevant weather for us. We discuss our routing and they advise against going over the icecap. We’d already really decided to hug the coast even though doing so would add time on to our leg. Ditching is something we’re mentally prepared for and it’s a perversely comforting thought that we are more likely to survive a ditching than a forced landing on the mountainous icecap. In truth, I think the realisation is beginning to dawn on both of us that if the engine stops we are highly likely to be dead but we suppress thoughts like that and just plan the various aspects of the next leg to mitigate the risk as far as we can. As we’re now in Greenland, we’re UTC minus 2 hours and the currency is back to Danish Kroner. We go to see an official (the airport manager by the look of his uniform) to settle our bill for fuel and landing fees. The total is a rather suspiciously round figure (and a large one at that). I’ve just gotten used to the conversion rate for Icelandic Kroner and I’m struggling to remember the exchange rate for Danish Kroner to get an idea of how much we’ve just spent. It turns out that the fuel was the most expensive that we would uplift over the whole journey but we’ve not much choice about filling the tanks to the top. We’ve had a fairly quick turnaround and are ready to set off within 30 minutes but the Saratoga starts playing up and won’t hot start. We spend 15 minutes trying everything we can to get her started, but the battery is beginning to sound dangerously low so we disembark and leave the aircraft to cool down. We decide to give it another 20 minutes and then have one last try, after which, we’ll be looking for a GPU as the battery probably only has one more start left in it. We don’t even want to think about how much they’ll charge us for a ground start so let’s hope she starts. Fortunately, at the next attempt, when everything has cooled down, the Saratoga starts first time and we trundle down the runway, backtracking to line up for a departure from runway 29. Kulusuk to Narsarsuaq – 3 hours 12 minutes – 435.2 NM After all the messing about trying to get the engine started in Kulusuk, we’re eventually on our way to Narsarsuq at 13.26 UTC. We route down the coast as planned but have major communications problems as we very soon find ourselves in a situation where we can’t contact anyone due to the mountain ranges and our relatively low altitude. The coastline is effectively blocking comms and there’s apparently no-one above us or anywhere near to relay a message for us so we continue making periodic ‘blind’ transmissions.

Typical Greenland terrain (and it gets a lot scarier as you get lower!!) We begin to realise that the notion of being a little safer by tracking the coastline and being able to ditch in calm waters close to the shore is a misplaced one. The mountains loom up ominously from the shore and the water is absolutely full of small icebergs which look insubstantial from a certain height but which are all the size of a small family car when you get closer to them. We don’t fancy a Ford Fiesta sized chunk of ice coming through the window if we ditch but wherever we look there’s simply no clear patch of water. As we look around, we realise that there is ABSOLUTELY NOWHERE to carry out a forced landing and have any chance of survival. This is quite a daunting realisation and it prompts us to change our routing and cut across the icecap in a direct line to Narsarsuaq cutting over 100 nautical miles off our route. As we fly over the icecap there’s quite a bit of turbulence which becomes so regular, Paul likens our passage to sitting in a tumble dryer! The scenery is again spectacular and troubling in equal measure and we are relieved to eventually establish comms with Narsarsuaq and arrive over their beacon at 9500 feet. Runway 25 is in use and we descend in the hold and take up position right hand downwind. However, some confusion on the R/T on the part of the guy in the tower means that he gets our call sign mixed up with the call sign of a Citation approaching from the West. We are probably the only two aircraft he’s handled all day and the whole episode results in the Citation getting very up close and personal with us. We know that we were in the right place and had been cleared as number one to land but that would have been small consolation if the Citation had wiped us out (as he very nearly did).

Right hand downwind for Narsarsuaq Nararsuaq is a notoriously difficult airfield to approach as it nestles at the top end of one of many long fjords at the SouthWest tip of Greenland. We were fortunate to have had perfect visibility and to be able to descend from the height we’d gained over the icecap to use runway 25. There have been a number of fatalities in the past, especially when flights have been approaching from the West for runway 07 and have chosen the wrong fjord. By the time their mistake is evident, the fjord has narrowed and the mountain sides have risen to a point where a 180 degree turn is out of the question and climbing over the mountains is equally impossible. Extreme caution is recommended if approaching this airfield in less than perfect weather. Just to reinforce how different it is from back in the UK, we were amused to see a warning notice advising caution as there may be icebergs on the approach to 07!!

Approach to runway 25 / Our hotel in Narsarsuaq / Narsarsuaq terminal and tower Narsarsuaq: population 160 (Human) 1.6 million (Mosquitoes). On the ground we are met by the mosquitoes again and a couple of locals who kindly offer to take us in their truck to the only hotel in the town. As we are driving along, I ask our driver how far it is to the town. He looks at me strangely and says “This IS the town” and then pulls over to a long building which it seems is the hotel. It’s only about 18.00 UTC (16.00 Local) so we check in to what turns out to be a very tidy and clean hotel. We have a bite to eat and then walk a couple of miles to go for a look around the small harbour just to the South of the airfield. There’s no-one around and the only sound is the heat haze and the mosquitoes. There are indeed icebergs in the bay and they sit there gracefully in crystal clear water which is so still it looks like a sheet of glass. I go down to the shore and put my hand in the water and, as expected, it’s freezing. I wonder how long we’d last in our immersion suits in water this cold? At one point there’s an almighty cracking sound and one of the massive ‘bergs which can be no more than 20 feet away from the shoreline rolls over in the water. It’s a slightly weird sight and the way the iceberg rocks around when everything else is perfectly still almost makes it look alive.

My very own bit of iceberg! We go back to the hotel to sample the beer and get talking to the barmaid who finds us somewhat more windswept and interesting than the locals and so ends up buying us drinks by the end of the evening. She’s absolutely delightful and bears more than a passing resemblance to Pocahontas (although she’s tired of hearing that). At her insistence, we sample a number of local liqueurs and shorts and learn a little about local customs – when and how these concoctions are drunk (some of which, frankly taste like the cleaner I’d use to get gunk off my motorbike chain!). Her Parents work here in Narsarsuaq but she lives and studies in Copenhagen and is just here visiting her folks and working in the hotel for the Summer season. Apparently, in Winter, everything shuts down here and the population falls to under 100. This place makes Kulusuk look like the big city!!

The barmaid- our very own 'Pocahontas' Reasonably early to bed with the intention of getting off early tomorrow and staying mindful always of the fact that we have to allow sufficient time to get the previous evening’s alcohol out of our systems. The forecast is good so we should certainly make Nuuk tomorrow. Day 5 – Tuesday 14th July. Total flying time 1 hours 57 minutes – total distance 279.4 NM Narsarsuaq to Nuuk – 1 hour 57 minutes – 279.4 NM The flying time to Nuuk is relatively short compared to some of our other legs and we take our time, getting airborne just before 11.00 UTC. We have to circle on takeoff to get the necessary height to get over the mountains to the North West. The visibility is excellent again and we decide to route to Nuuk almost directly which again involves flying over part of the icecap. We’re getting quite blasé about this now. Emotionally, I know that if we crash, we’ll never be found but intellectually, I know that there’s no reason for the engine to stop. We have full fuel, the oil’s topped up, everything’s in the green and we’re flying at the optimum cruise settings and not straining the engine. I voice the opinion that there’s very little that should go wrong and paul Y goes absolutely bonkers saying that I’m tempting fate and that I have now guaranteed engine problems. I didn’t know he was so superstitious. Of course, now that I know he’s unhappy about me ‘tempting fate’ I try to do it regularly just to wind him up.

Glacier, lake and mountains on the way to Nuuk We are routing to the East of an airfield called Paamiut situated on the western coastline about half way between Narsarsuaq and Nuuk and we listen out on their frequency and even consider stopping off to get another exotic stamp in our logbooks but we elect to press on and get to Nuuk as early as we can. The scenery is again spectacular with massive iceflows, turquoise, silt-filled lakes, gigantic mountains and massive valleys and chasms – any one of which could easily swallow a little Piper without trace.

Approach to Nuuk runway 23 - right hand, downwind We make contact with Nuuk approach and are cleared to join right hand downwind for runway 23. On the ground, we’re met by mosquitoes again (about 6 million of them this time – it’s worse than Kulusuk or Narsarsuaq). On the apron I put all my paperwork on the wing whilst I try to disentangle myself from my immersion suit. At that point, a helicopter takes off and flies directly overhead scattering all my paperwork all over the airfield. Receipts, charts, copy flightplans, plogs etc. are flung to the four corners of the busy apron and we spend 15 minutes trying to recover them assisted by an army of Inuit airport workers. All this is going on while we are trying to ward off the clouds (and I do mean clouds) of mosquitoes. We get back most of the paperwork but some of it has blown over the perimeter fence and is lost forever. I just hope there’s nothing critical gone over the fence. We get to the check-in and the office staff are still tittering and us. The explosion of paperwork and us scurrying around the apron must have been quite an amusing spectacle.

Paul Y casts off his immersion suit at Nuuk (my papers which are going to be blown away are on the tail) / Nuuk termunal building and tower Nuuk is the capital of Greenland with a population of about 15,000 so we’re expecting a change from Narsarsuaq and Kulusuk and it certainly is different. The town is some way away from the airfield (about 2 or 3 miles) so with all of our kit (which we’re not happy about leaving unattended in the aircraft) we need to get a taxi into town to a hotel that’s been recommended to us. The taxi fare is obscenely expensive but we don’t care as we’ve got a day of exploring Nuuk ahead of us. We get into the hotel, get showered, plug in all the camera, GPS and phone batteries to recharge and then send off an e-mail update from the reception area - as we’ve been doing to friends and family at every stop so far. Then we go out to discover Nuuk. We’ve telephoned home at every stop so far too. In Iceland, my mobile worked OK but in Greenland so far, it’s been necessary to use public telephones. Our mobiles don’t work here and, unlike Kulusuk and Narsarsuaq, there isn’t a public phone to be found anywhere in Nuuk. In fact, people look at us like we’re a bit odd when we ask for the location of the nearest public phone. Everyone uses mobiles. We end up making a very short but nonetheless expensive call home using the Satphone which is charging back in my hotel room. We’re a long way out now and it’s reassuring to confirm that all’s well at home before (perhaps selfishly) continuing on our adventure. I’d love to claim that we went on a cultural journey of exploration but I’d be lying! We’ve now got coins and notes of all sorts in our pockets and confusion reigns between Danish Kroner (about 8 to the £) and Icelandic Kroner (about 200 to the £) we’re getting to the point where we don’t know if the food, beer and accommodation is cheap or expensive and as the beer flows, the effort of doing the mental arithmetic necessary to convert back to Sterling becomes tiresome. Oh well, we’ll just have to work it all out when we get home.

Downtown Nuuk I have to make special mention of the social life in Nuuk. Maybe we’re just attracted to the wrong places but at the bars we went in (and we went in lots!) it looked like the lunatics were about to take over the asylum! Some of the people there were absolutely out of control. They were all overly friendly but seemed to be under the influence of a considerable amount of booze. I’ve been to cut off villages North of the Arctic Circle in Alaska and since they abandoned the nomadic way of life, the indigenous population there have nothing to do but procreate and drink themselves into a stupor (fortunately, booze eventually dampens the ardour otherwise there’d be more Inuit Indians than Chinese). Nuuk reminded me a little of this but that surprised me as, although it has a population of only about 15,000, it is, after all, the capital city and I expected it to be a little more cosmopolitan. We went to one bar which we’d been told about by an American guy who we met in Reykjavik. He worked in Nuuk and was holidaying in Iceland. He recommended the hotel in Nuuk and told us that we must visit the ‘Yellow Bar’. That’s not its proper name but it’s in a very large wooden building which is painted bright yellow and is visible from quite a way off (in fact I’m surprised we didn’t see it on the approach!) Knowing that we weren’t flying until mid-morning the following day, we decided to get well oiled in the afternoon at a selection of bars. Then, after a meal (which was one of the best I had on the whole trip) it was back to the hotel for a quick spruce-up and then we spent most of the night in the Yellow Bar. I nearly got a stiff neck from shaking my head in disbelief at the antics of the locals. I like a drink as much as the next man but I’ve never been in the company of so many seasoned drinkers before. When the bar staff refuse to serve them any more they will pay a stranger to buy drinks for them. When that tactic begins to fail, they will simply steal your beer if you don’t keep your hand on it. The Yellow Bar is a bit of a cross between the sort of place you’d expect to see in an Indiana Jones movie and Patrick Swayze’s Roadhouse – a live band (German, I think, and I bet they sacked their agent when they got home!) behind a mesh screen to stop bottles being thrown at them, lots of fights (but with people continuing to dance around the fracas) and general mayhem.This was only a small part of what went on in that bar and I won’t even start to describe all the events of the evening. I do recall being challenged to a fight in the Gents by a wiry, little Inuit Bruce Lee look-alike. He struck up a martial arts stance and stood stock still until I'd finished my ablutions. Once I responded in a particularly aggressive way, he became my best mate for the rest of the evening. I saw him fighting again later that night with a big Danish sailor twice his size so I think he liked pain. In fact, his Wife or Girlfriend subsequently punched him in the eye when I was watching him on the dancefloor. I don't know how he'd upset her but as his eye swelled visibly, he broke into a grin which he didn't seem to be able to shake off. I was beginning to get the impression that some of these people were a bit odd!. There was also the incident where the very attractive German female lead singer of the band tried to stamp on an Inuit woman’s head with her stilettos after having what looked like red wine thrown on her white outfit through the mesh whilst she was performing. She had to be pulled off by the bouncers. Whilst all this is going on, the backing group just continued to play as if nothing was happening and people just carried on dancing, leading me to believe that this sort of thing is a regular occurrence. She was a feisty one that singer and it amused me to see her just go back onto the stage and carry on singing as though she hadn’t just tried to kill someone. It was all great fun and we loved the place although we kept relatively sober to ensure we were clear-headed enough to stay out of trouble. The Yellow Bar may be the sort of place where if an unwary tourist goes missing, they’ll never find the bodyparts.

The infamous 'Yellow Bar' - it looks harmless, doesn't it? / Some of the Locals When I woke up on Wednesday morning, the events of the previous evening seemed dreamlike and highly improbable but we both remembered most of the same things so it must have actually happened. Day 6 – Wednesday 15th July. Total flying time 8 hours 8 minutes – total distance 1040.8 NM Nuuk to Iqaluit – aborted due to weather We’d set off early with a view to getting to Iqaluit and back to Nuuk in one day (another night at the Yellow Bar seemed enticing and frightening in equal measure!) However, the weather at our destination is not looking good. We get about 50 NM out from Nuuk and get a weather update for Iqaluit. It’s not going to happen as there’s fog and we both know that to push on would be simply stupid. Doing a 180 and deciding to abandon the leg to Iqaluit was one of the hardest things we’ve had to do but the decision was made easier by the fact that we knew that technically, we’d already flown the North Atlantic (from Nuuk to Iqaluit is the Davis Straight and below it is the Labrador Sea) and we also knew that we couldn’t possibly encounter any terrain that was more hostile than that which we’d already traversed. Therefore, the trip to Iqaluit was just ‘more of the same’ and so we decided to head South and West and to home. Nuuk to Narsarsuaq – 2 hours 4 minutes – 265.2 NM Nuuk to Narsarsuaq is uneventful and is just the reverse of the outward leg. I find the airfield without any trouble and we descend in a spiral pattern to approach, again right hand, down wind for 25. The flight from Nuuk has been at an average of 9500 feet but that has only given us a couple of hundred feet clearance over the icecap. The winds were the opposite of those forecast and we’ve had to contend with a headwind for most of the leg. This is the sort of terrain, riddled with huge crevasses, where numerous WWII aircraft went missing, never to be found, when being ferried to England as part of the war effort. Looking at the landscape close up, I can understand why airframes could be lost without trace even if regular position reports are being made. We land (without conflicting with jet traffic this time!) and fuel up. The Saratoga is now regularly misbehaving if we try to hot start it so we’ve had to get used to switching everything off and leaving it for 30 minutes before trying a startup. Narsarsuaq to Kulusuk – 2 hours 49 minutes – 362.2 NM We just want to get home as soon as possible now so we’re planning to get to Kulusuk and on to Reykjavik (as we don’t fancy staying in Kulusuk overnight) in what’s left of the day. This will be tight so we’d better get our skates on! We decide to take an even more direct route over the icecap than on the outward leg and, rather disconcertingly, our charts show certain areas which are unmapped and state “Unexplored area. Height believed not to exceed 13500 feet”. If we venture too far into the interior we could encounter problems as we’re not equipped with oxygen. That, of course, assumes the Saratoga can make 13500 feet. Its service ceiling is higher than that but I’ve never been that high in it so it’s all theoretical. For most of the leg, we can manage with 10500 feet and we encounter another worrying phenomenon when the throttle is firewalled and the ground is coming up to meet us faster than the aircraft seems capable of climbing. At one point we could have been no more than 100 feet above the ridges and crevasses and there’s quite a challenging downdraft from time to time. At least there’s no danger of us falling asleep. As we’ve not had time on the ground to find anywhere to eat, we have a tin of cold baked beans and sausages from our supplies. The autopilot is in so I can concentrate on my meal but both of us are getting a little tired and so we end up having an argument about Paul Y discarding his empty beans tin in the back of the aircraft. The whole of the rear section is a total mess and I’m getting a bit fractious about the abuse my aircraft is suffering.

The Greenland icecap from 10500 feet / The rear cabin is starting to get a bit untidy! We press on to Kulusuk, by now, ignoring the terrain, the snow, the ice and the downdrafts. We speak to Kulusuk and hear a commercial flight inbound to them. This time we are approaching straight in for runway 11 and again, I would have had difficulty picking out the brown gravel runway from the background if we’d not been number two to the commercial flight which showed me the way. We’re on the ground and want a quick turnaround which we get but again, the Saratoga is playing up and won’t start.

Approaching Kulusuk / A little closer with runway 11 on the nose / Runway 11 straight ahead Kulusuk to Reykjavik – 3 hours 15 minutes – 413.4 NM We arrived at Kulusuk at just after 17.00 UTC and we are informed that the airfield at Kulusuk closes at 19.00UTC and that we must be taxying 15 minutes before that. The usual 30 minutes down time doesn’t do the trick and the Saratoga still won’t start. There is little flexibility around the airfield closing time although the guys in the tower (who remember us from the outward leg) say they can allow us an additional 5 minutes. The bastard aircraft simply won’t start and before we know it, we’ve only 10 minutes left before an enforced stay either in the Kulusuk Hotel or in our sleeping bags if it’s fully booked. We REALLY don’t want to stay here.

Leaving Kulusuk / Approach to Reykjavik It’s a straight line over the water to Reykjavik and the water is just water (no ice in it!) so the pressure’s off a bit. The weather is closing in slightly as we get closer to Iceland but we pick out the airfield from a distance and we relax slightly, knowing that we’ve covered over 1000 nautical miles in a single day and that we can overnight in Reykjavik and be home in time for weekend. However, our troubles are not over yet as when I lower the landing gear on approach, we only get two greens and we have a gear unsafe siren blaring away. It would seem that the nosewheel is not down. I don’t want to sound macho but I wasn’t the slightest bit apprehensive about this. It’s amazing how quickly one’s mind works and I’d already run the various scenarios in my head by the time I radioed the tower to tell them we might have a problem. I was actually quite excited as I’ve never had to crash land before and perversely, I was quite looking forward to damaging the aircraft on landing. After all, we were back in civilisation, the aircraft was fully insured, we’d all but completed our trip and I’d absolutely no doubt that we would walk away from the aircraft unhurt with a great story to tell.

Only 2 green lights and a red 'gear unsafe' indication We recycled the gear, tried the emergency gear dump and did a flyby of the tower who confirmed that the nosewheel appeared to be down. Nevertheless the absence of the third green light and the (by now, very irritating) gear unsafe siren still indicated a problem. We knew it wasn’t just a blown bulb as the nosewheel light flickers but stays off. ATC allowed us to circle to approach the main runway (which seemed strange as we’d have blocked it for a while if the wheel had collapsed) and we were followed down the runway by fire engines (another first!). I asked Paul Y to take a photo of the two greens as we were on finals and he looked at me as though I’d gone mad. I was actually having fun at this point but Paul Y was being typically focussed and serious and I'm sure wanted to be hands-on. However, we'd agreed before we crossed Greenland on the way out that he would handle any emergencies when he was flying the outward leg and I would handle emergencies coming home so I got to be in command which I'm sure was frustrating for Paul Y as we're both control freaks really. We landed on the mainwheels and kept the nosewheel in the air for as long as possible. When it eventually touched down, it held and our subsequent positioning onto the apron outside Birk Air Services was a total anticlimax. We disembarked and had a cursory look at the nosewheel but by now it was going slightly dark so we knew we’d have to have a closer look in the morning. So, off to the hotel and out for a well deserved wind-down drink. Day 7 – Thursday 16th July. On the ground in Reykjavik effecting repairs We’ve had another night out on the town in Reykjavik. We’re almost locals now! Somehow the novelty of the place is wearing off and, looking at the situation more objectively (and soberly), there are a few indications that the Brits are not really liked over here. The bar which we’d been in regularly had a cartoon on the wall about being “Lost in Iceland” and a barb about “Can you keep up with the Vikings?” showing a boozy chap in Union Jack shorts. I’m sure it wasn’t intended as such (as we weren’t the only Brits there) but it felt like a personal insult. The other thing we noticed was a few people going around in t-shirts which read “Stab me – I’m a tourist”; funny ? I didn’t think so but perhaps I was just getting tired.

Two of the Barmen at one of the pubs in Reykjavik - they look a bit unfriendly but they were OK actually / The drawing I took issue with. If I'd not been so tired, I might have taken up the challenge .... Vikings?....Ha! We’re up early on Thursday and we ask Birk Services if they can arrange for an engineer to come and have a look at the landing gear. They say they’ll try but don’t sound too hopeful. The maintenance facility is right next door to the apron so Paul Y walks across to try to solicit some assistance. He enters a massive hangar with numerous aircraft of all shapes and sizes in various stages of assembly. There’s only one thing missing from the picture….. people! There isn’t an engineer in sight and the place is like the Marie Celeste. It would appear that aviation engineers are much the same the World over. All those aircraft owners are paying for some very expensive tea breaks! We realise that we will be waiting forever if we simply sit back and wait for an engineer to arrive so we get out the toolbox and start to see if we can diagnose the problem. The nosewheel seems to be locked firmly into position so logic dictates that it’s simply a problem with the electrics. The first thing we do is to pull the fuse for the gear unsafe siren as every time we switch the Master on it blares away and is slowly driving us both insane. On close inspection, the problem appears to be a microswitch which isn’t contacting as it should. There appear to be two on the nosewheel – a ‘negative’ one which contacts when the gear is retracted and breaks contact when the gear is lowered and a ‘positive’ one which has a broken contact when the gear is up but makes contact when the gear is lowered. It is this ‘positive switch which seems to be the problem as it is clearly bent out of shape. We surmise that the damage must have resulted from the gravel bouncing up from Kulusuk’s runway as we taxyied at a faster than normal pace to get away in time. The plate on the microswitch would only have had to be moved slightly by a stone impact and then the retracting wheel assembly would have twisted it even further. This seems to be the only plausible explanation.

Cowling off - now we can see the problem / The bent microswitch I can see the switch but I can’t easily get to it. In order to do so, we have to take all of the cowling off the front of the aircraft. When we get access to the switch and it’s bent back into shape, it contacts and, hey presto, when we replace the siren fuse there is a blessed silence and the problem appears to be solved. It took several hours for us to diagnose and resolve the problem and it takes another hour or so to put the aircraft back in good order so most of the day is gone. We dispense with the usual amounts of beer and socialising – it’s becoming rather tiresome. We simply go for a late afternoon meal and go back to the hotel. When we get back to the apron, there’s a beautiful Air Iceland Dakota just taxying in and I get a few photos of it. We go to bed early ready for an early start next day.

Mike Tango alongside a Danish Air force Hercules transport plane Day 8 – Friday 17th July. Total flying time 6 hours 37 minutes – total distance 937 NM Reykjavik to Stornoway – 4 hours 19 minutes – 589 NM (the longest single leg) Well, just about everything goes wrong this morning. The weather in Vagar will prevent us getting in (fog again) so we decide to go directly to Stornoway. We plog this out very carefully and realise that we can do it but we’ll be on minimum fuel reserves if the forecast wind turns into a headwind. We know from personal experience on the trip so far that the wind is rarely as forecast so we plan the leg based on several wind scenarios. We’re now more than familiar with the performance of the aircraft and the best cruise settings and the Garmin will give us an accurate groundspeed once we’re flying so we can calculate the Crit Point –PNR en route. Nevertheless, the leg will be the longest one yet at nearly 1000 nautical miles and in that distance over nearly 5 hours of flying, the weather and the wind can easily change and catch us out. I hate to mention the ferry tank again but the absence of excess fuel adds a different dimension to the leg and I can feel a little apprehension in the pit of my stomach. Mike Tango refuelled and the two Pauls ready to leave Reykjavik After all the drawing lines on charts and planning the fuel burn, we turn up at the aircraft to pre-flight it and find that it’s not been fuelled. We’d asked Birk Services to arrange a refuel yesterday. They’ve let us down for the first time. We go to the reception and find it manned by a young chap who is obviously a stand-in as apparently some personnel are off. He can’t find our account and we can’t leave without paying. He’s also unsure how we can get fuel and doesn’t seem too confident about filing our flight plan. The refuelling bowser is nowhere to be seen so we will have to taxi round to the fuel pumps but the aircraft has been standing for nearly two days now and we kept putting the master switch on (thereby draining the battery) whilst we were trying to resolve the landing gear problem. We fear that a start-up and a short taxi to the fuel pumps might drain the battery even further and clearly, we can’t keep the engine running whilst refuelling. We’ll just have to hope that there’s enough juice left in the battery for a second start. We get round to the pumps and have to wait for ages as it’s not self-service. The lad at Birk Services needs to come out and authorise the fuel uplift. We’re back in our immersion suits at this point and I’m sweating my arse off as we have to walk back from the pumps to the reception at Birk Services to pay the bill which now has to be adjusted for the fuel we’ve just taken. We’ve left the Saratoga at the pumps blocking anyone else from getting in so I’m agitated and want to get back there and fire it up asap. Also time is ticking away and if we’re not careful, this cockup with the invoice will prevent us getting home. I can deal with being delayed by the weather but if we’re thwarted by paperwork, I’ll not be happy. We file a VFR flight plan which will take us on the most direct track and, as we’ve done before, we insert latitude and longitude co-ordinates on the flight plan showing where we are going to cross the FIR boundary. We don’t know it at this stage, but , yet again, the VFR flight plan is next to useless and, although it’s accepted, the intended routing is going to cause us problems. I’m feeling a little agitated at this stage as I know that we have to get going and I’ve been frustrated by the unusually poor service from Birk Services. I’m not at all sure that we won’t bend the microswitch again when we retract the landing gear, we’ve got the longest leg so far in front of us, the last payment for the hotel, handling, fuel etc here in Iceland has just about maxed out my credit card and I’m still sweating like a horse in this suit. There’s a feeling that we should have been airborne about an hour ago and this all leads to a rather hurried departure. Fortunately, the aircraft starts (but reluctantly) and I’m sure if we’d started up at the pumps to taxi back to the apron before departure, we’d have been looking for a GPU to start us and incurring additional cost and wasting more time in doing so. So, we’ve been lucky- but then our luck begins to run out. We call the tower for taxi clearance but their response is almost unreadable. We switch to box 2 but still can’t raise them. We decide to do the run-up checks in situ to try to save a bit of time and hope the radios sort themselves out. On the mag check we get a wicked RPM drop and spend a few more valuable minutes trying to lean back and burn off what we hope is just a bit of plug fouling. Maybe the high RPM check helps but fortunately we get the tower on Com1 and we are cleared to taxi from the Echo taxiway across runway 13 for a 06 departure. It all starts to go even more wrong at this point. First of all, we head the wrong way down the Echo taxiway and nearly stumble into the 01/19 runway. We do a 180 after being corrected by ATC and trundle along to 06 hoping we’re not going to be kept waiting too long as we’re burning fuel which we can’t afford to lose. As we taxi onto runway 13, a different voice from the tower tells us that we were not cleared to enter 13! We're highly indignant as we know we were cleared to cross! Anyway, by now, I’m taxying almost fast enough to get airborne and we’re nearly at the junction of 13 and 06 so there’s precious little the guy in ATC can do except be pissed off at us (and he sounds like he is). I’m getting pretty pissed off too at the injustice of this – I’ve just been accused of backtracking a runway without ATC approval when we both heard the clearance. We end up holding behind a Cessna who’s taking his time doing his power checks and we’re burning more and more precious fuel and going nowhere. We’re now on 06 and rolling for takeoff. As we get airborne, I’m a little worried about the way we’re climbing (or, rather, NOT climbing!) The trees at the end of the runway are looming large and we only just clear them. I can’t figure out what’s wrong until I look down and realise that the friction nut wasn’t tightened and the propeller lever had vibrated back about half way. I haven’t tightened the nut and I haven’t kept all the levers firewalled with my hand. Another basic error which was probably caused by rushing and trying to do the preflight power checks from memory rather than using the checklist. The verbal exchange with ATC regarding our alleged incursion onto runway 13 was also a distraction which was being replayed in my head when I should have been concentrating on other things. Anyway, we’re off and the gear appears to have retracted without any problems. We’ll find out at Stornoway whether we’ve cured the problem. We get on heading, level out at 4000 feet and prepare for a long flight. The visibility is poor and as we move away from Iceland, communications begin to get difficult. We are relaying position reports via British Airways (callsign ‘Speedbird’) jets overhead and are positioning to cross the FIR boundary at the co-ordinates entered in our flightplan. This takes us slightly into the Shanwick Oceanic Control Area and we get a very late call from Reykjavik Control saying that Shanwick will not allow us to continue with our intended route and that we must divert to the East to route around the OCA. We are becoming increasingly worried about our fuel and I am quite angry at Shanwick’s forcing us to change direction, thereby increasing our flying time and using up valuable fuel. We had filed the flight plan in good time before our departure and late en-route diversions such as this, particularly when combined with an unforecast headwind (which we’re now battling with), could prove very dangerous if we’re on minimum reserves. I doubt that we would have interfered with any of Shanwick’s traffic at 4000 feet and it’s most likely that they just didn’t want to have to worry about us on their screens. We look at the GPS groundspeed numbers very carefully and Paul does repeat Crit Point PNR calculations taking into account that the headwind which we have encountered would at least be of some assistance if we had to turn around and head back to Iceland. We calculate that, with the new heading and the headwind, we have enough fuel to make Stornoway….just. We’re not quite past the point of no return but I have to admit that if we had been and the revised routing had caused problems, I’d have just continued on the direct path and worried about sorting it out with Shanwick over the R/T. I’m not going in the drink just so a controller can have another tea break! Chances are, if we’d had to explain our situation, they would have accommodated us anyway. We’re Mode S equipped and should be visible to them. However, we comply with their request and dogleg around the OCA. Eventually, we switch from Iceland to Scottish Information and we feel we’re getting closer to safety. The cloudbase is pushing us lower and lower but we’re nearly over land and I know that Stornoway is just over the horizon. We’ve got Stornoway on the radio and we’ve got joining instructions for runway 06 which I’ve already figured out I can join on left base. A few minutes later and we’re back over UK land and most of the water is behind us so I relax. As it happens, I relax a little too much as I visually position myself perfectly for a left-base join to the disused runway. I’m at 0.5 mile final by the time Paul says “ Is that a big X down there?” Oops! I haven’t looked at the GPS or the DI once since getting over land and I haven’t set the DI bug on runway heading and cross-checked when turning final as I would normally do. I peel off to the right to try to correct onto the proper runway and in doing so, nearly allow the airspeed to decay into the stall range. I overcompensate, push the throttle forward and the nose down and we very quickly accelerate to the point where I’m exceeding flap limit speed (I’ve got 2/3rds flap still in) and we’re down at 500 feet. The approach is probably one of the worst I’ve ever done in my life and if I was trying to convince myself that I wasn’t fatigued and exhausted, I was clearly wrong. The guys in the tower have been watching my approach but are totally unruffled and when I get up there and explain that I’m not usually such an idiot, they just smile and one of them says, “We were wondering what you were doing but we thought you’d sort it out.” I’m sure they’d have let me land on the disused without saying anything and had a laugh about it later. Stornoway to Liverpool – 2 hours 18 minutes – 348 NM We get the weather and it looks as though the last leg is trying to kill us. We’re in two minds whether to go or stay in Stornoway but I have to admit that ‘get-home-itis’ results in the decision to launch. Some may tut, tut and say this is poor judgement and bad airmanship but I would disagree. We know the weather is forecast to remain clear at Stornoway and we are now over familiar territory with a lot of alternates which we could set down at if necessary. It’s not bad judgement to set off (provided it’s all within legal limits) but it is bad judgement to keep going into deteriorating weather and be too stubborn to do a 180 if necessary. This is what often kills people and, believe me, I don’t want to die after all we’ve done in the last week. We know the bad weather is running down the coast and so we decide to route to the Isle of Man (over yet more water!) and head in to Liverpool from the West. We’re both instrument rated and the Saratoga is a well-equipped IFR platform so we can do a radar vectored or a procedural ILS approach to Liverpool if necessary. We fly to the Isle of Man in relatively clear weather. As we head East to Liverpool from the IOM beacon, the weather ahead looks dodgy but as we approach Liverpool, the poor visibility seems to lift slightly (although it is now raining – the first rain we’ve seen for a week) and we position for a visual approach to runway 27. That’s it – we’ve done the whole thing VFR! Back to Liverpool and the rain. The hangar doors are closed and there’s no flying going on. The GA apron is completely deserted so there are no brass bands to welcome us home. We touch down on the wet runway and taxi in. We leave Mike Tango looking rather forlorn in the gloom but the aircraft has served us well and we are tired but pleased and relieved.

Stone chips on the elevator (presumably from Kulusuk) / Back on the apron at Liverpool and lookin folorn in the wet We burned 1604 litres of fuel, spent £5707 in total (not counting beer money) and flew 4082 NM in 29 hours 58 minutes over 8 days at an average groundspeed of just over 136 knots. It was an amazing experience (particularly Greenland) and I’d do it again tomorrow (preferably in an Antonov AN-2 with a large ferry tank and from New York to Lithuania straight over the water!) They say a Man is eventually the sum of his experiences and this was a significant one. It started as a self-indulgence but became a formative and humbling trip. The memories will stay with me forever.

Back home - very tired, unshaven and sweaty P.S. G-BKMT has been sold since our trip. It was a very reluctant sale as I feel an affinity with the aeroplane which wasn’t there before our trip. However, the cost of the EASA mandated ‘back-to-birth’ inspection for the annual inspection and the issue of an ARC just before our trip nearly crippled me and I simply couldn’t afford to keep the Saratoga and my other aircraft – a 1943 Texan. The Saratoga served us very well and someone has acquired a very nice aeroplane which has been places most UK registered aircraft have never seen. I don’t know the new owners as the sale was through a broker but I hope that Mike Tango has gone to a good home. Paul Squires

|